In this book extract, New York Times bestselling author Joanna Gaines on how she learned to break free from years of hiding her true self, and continues to challenge untruths she has believed

I entered adulthood carrying around this black-and-white way of seeing the world. I saw through this lens that convinced me there was only one way to go about living. But then I met and married Chip, who is basically a poster child for doing things not wrong or right, but some other way entirely.

My narrow outlook threw us for a few loops in those early years, but it was clear that I’d brought into our marriage certain ways of thinking, of living, of managing money based on how my parents raised me. We both did. But while Chip saw them as opportunities to be refined and challenged, for a while, I hid beneath the weight of them. Not to mention that Chip and I are different in seemingly every way, except the ways that matter most to us.

If his default setting is risk, mine is safety. In a matter of months, he must have blown up every plausible ‘right way’ I thought kept the world spinning. Remember, different wasn’t something I trusted. Not for a while, at least. For a while, I lived by the rules I thought people wanted and expected: polished and put together, resisting anything that would make me slip out of the version of me I was presenting.

By default, there have been times over the years when I’ve unintentionally put Chip into the very box I’d squeezed myself into as a little girl, the box the world can make you feel as though you need to break yourself down in order to fit into. But the more effort we put in to understanding how the other worked, the more grace there was for how we were different. Fewer expectations were exchanged. Less reshaping of the other based on our own formation.

I saw, firsthand, the value of loosening my grip on a few things I’d always believed. It became clear to me that I had a choice to make. I could continue to stay anchored in place, tethered only to my version of right and wrong, thinking there was only one way to do anything, while the things I longed for most— connection, belonging, understanding—grew dimmer with distance. Or, to put it simply, I could choose to see the world in color.

When and why I learned to hide

I’ve been thinking about the place this perspective of right and wrong took root in me. It wasn’t within the walls of my childhood home. My parents let me live pretty freely. They were affirming in who I was and everything I did. My dad showed me this in his steadiness. Whenever he was in the room, I felt safe and secure. Like my feet were firmly planted. My mom was the nurturer, always present. Her love was the kind you could feel.

The thing was, when I was being teased and excluded at school it was because of my heritage, because of the way I looked and how I was different—and I couldn’t bring myself to share that pain with my mom. It was her heritage too. I didn’t see the point in both of us hurting. So I shouldered it alone, and I kept it to myself. Hiding became an art. At school, I tried hiding the culture I came from. At home, I tried hiding that anything was wrong at all.

This bred an instinct to perform, to shape-shift everywhere I went. Even with my faith, I believed at an early age that God’s love was conditional. I imagined that he was up in heaven grading me on every thought and every move I made, nodding his head in approval when I performed well. I became dependent on how it felt to do and be good, and then basically created a scorecard system that I handed to God at the end of every day.

I was a kid still, and not yet self-aware enough to ask those around me whether these rules I’d learned to live by were actually from God. It wasn’t until college that I started to see things differently because I was noticing that it was affecting my worldview—I was chafing against the idea that everything was black and white, right or wrong, and I had this nagging sense that I was missing the better picture. Of God, yes, but the world too.

Learning the truth about God—and myself

I regret how deeply I let that false idea fester in me. But when a timid, rule-following little girl is given a set of religious rules and legalities, she’s going to cling to those things with every inch of her. And she did, for a while. But once I began unraveling, slowly, that misguided view of God, the most beautiful thing I learned is that he does love me, only freely. During the season I lived in New York, I was able to truly experience the heart of God—whose kindness and grace drowns out rules, and whose love for me is unconditional. For me, God is the deepest anchor in my life. He is my constant, the way I orient everything around me.

Once I set that foundation of the truth about who God is, it sent me searching for the truth about myself too. Because if I’m being honest here, when it comes to perfection and performance, those are weights that can still pull me down.

The anchor of perfection is one you’re always going to see me knee-high in the sand trying to yank out. It’s another one that was dug in the ground beneath me for as long as I can remember. In some seasons, it’s crippling. In others, it’s led me to a deeper place of creativity. It’s a vice and a gift. Sometimes both at the same time. But it’s had its moments, when it’s wreaked havoc on my sense of self and worthiness. It can skew the person I see when I look in the mirror, the qualities I believe I have to offer.

The only way I’ve known to get a handle on these anchors is by checking in every now and then. When I sense that something untrue—an idea, a belief, a way I’m seeing myself—has made itself at home in my head or in my heart, I try to quiet it with honesty. Sometimes I’ll write it down; other times I’ll say it in a whisper. Every now and then, I feel willed to speak it as loud as my lungs allow: “I am not who those kids said I was.” “I am worthy without performing.”

When I sense that something untrue…has made itself at home in my head or in my heart, I try to quiet it with honesty

There have been moments when questioning aspects of my identity, religion, or my narrow sense of right and wrong have felt like a surprise airstrike on my sense of self. But a thousand other quieter instances, too, have opened my eyes to outdated ways of seeing myself. In those moments, it often takes just a gentle nudge, asking myself, Am I anchored in truth with how I’m viewing myself? God? Others?

That’s how I decide what needs releasing—what I need to be reaching for to ground me—as well as what simply needs strengthening. Sometimes ugliness rises to the surface—a few things I didn’t expect. But almost always there’s also something beautiful on that list, a reminder, a truth I’d forgotten was there to hold on to. I’ve learned to do this exercise often enough, not always with the intent of changing everything but of challenging these things I let anchor me.

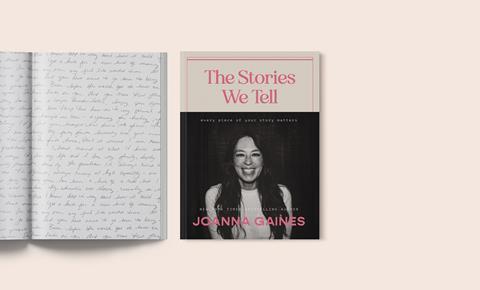

The above is an extract from Joanna’s new memoir The Stories We Tell (Harper Select). Follow her @joannagaines

No comments yet