Dr Sheila Akomiah-Conteh unpacks the origins and teachings of the little-known 19th-century Slave Bible

Throughout human history, religion has been wielded as a tool to enlighten and to darken minds, to give hope as well as to crush it, and to give life as well as to take life. In fact, in many contemporary societies, the widespread disdain and rejection of religion by some people is due to its association with negative and dark histories.

Christianity has not been immune to this tendency. The Bible has been used in the past and present to perpetuate atrocities and condone odious social practices such as wars, enslavement, colonialism and racism. Hard as it may be to face, this fact cannot be overlooked by Christians. One significant but little-known example from the era of slavery and colonialism was the crafting and utilisation of the Slave Bible in the early 19th century in the name of Christian mission and evangelism.

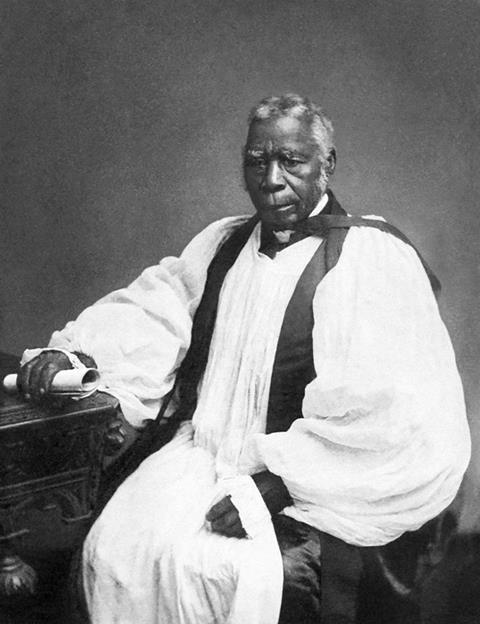

In 1807, at the cusp of the abolition of the slave trade throughout the British Empire, a carefully abridged version of the King James Version of the Bible was produced in London on behalf of the Society for the Conversion and Religious Instruction and Education of Negro Slaves in the British West India Islands. This Anglican-affiliated missionary society was founded and headed by the Bishop of London, Beilby Porteus, a key abolitionist. Originally titled Select Parts of the Holy Bible for the Use of the Negro Slaves in the British West-India Islands, it was not a new translation but rather a heavily edited version designed to serve a specific purpose during that dark but improving period of human history.

The timing of the publication was decisive and alluded to the purpose behind its creation. It seems that the commissioners of the Slave Bible understood the reality that the enforcement of the Slave Trade Act would be controversial and inconsistent, considering Britain’s then lucrative and bustling Caribbean slave colonies. Therefore, the manuscript was specifically intended “For the Use of the Negro Slaves in the British West-India Isles”. The British West Indies (BWI) were colonised British territories in the West Indies and included Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis and Trinidad and Tobago among others. Ironically, although an abolitionist project, the Slave Bible omitted many of the verses that abolitionists might use to back their case, and drew attention, instead, to key pro-slavery verses.

Hidden agendas

Although the push to educate (in literacy) and evangelise slaves was the Society’s defining cause, the underlying purpose of the Slave Bible was to control the spiritual and psychological lives of enslaved Africans. Christianity was wrongly used as a tool to reinforce their station as slaves, and to sustain the institution of slavery in the West Indies.

Literacy and Christianity were two things that most slaveholders deliberately withheld from their enslaved persons during this time. Both were seen as dangerous due to their potential to inspire slave uprisings. The full teachings of the Bible, with its themes of liberation, equality and freedom, posed a threat to the power dynamics of slavery. This fear was realised with the successful Haitian Revolution (1804) and multiple uprisings in the US North and South. If there was one thing white slaveholders, radical abolitionists, formerly enslaved persons and advocates for reform agreed on, it was that literacy was power. A slave who could read and write could: make false day passes and escape North; read the Bible and create syncretic religions that inspired revolts; educate themselves or use their literacy to plan and coordinate multiple escape attempts. So, refusing to let slaves read the Bible was a major precaution.

Although the intentions of the editors of the Slave Bible are not entirely clear, the book might have been intended by British missionaries as a way to reassure planters in the British Caribbean, who were often reluctant to convert their slaves. If enslaved people converting to Christianity was thought to undermine slavery as an institution, then a text that sought to use Christianity to reinforce slavery could have been a method to deal with that. To this end, Bishop Porteus made a convincing case in his 1808 letter to the governors and plantation owners in the British West Indies, highlighting the economic and spiritual benefits to slave owners who allowed his missionaries access to evangelise their slaves. In this lengthy letter Porteus argued that plantation owners should allow their slaves to receive Christian religious education so that their morality, particularly their sexual inclinations, could be harnessed with the hope of producing more offspring for their masters. More enslaved babies would lead to more slaves, more labour (since they couldn’t buy any more slaves from Africa by law) and more profit. He added that:

“Penal laws may certainly be enacted by the colonial legislatures, prohibiting illicit connections among the Negroes and requiring them to be united by legal matrimony to one wife. But human laws, it is to be feared, will be but a feeble barrier to the ardent and impetuous passions of an African constitution, and very incompetent to contend with the strength of inveterate and long indulged habits of vice. These can only be subdued by moral restraints, by new principles infused into the mind, by the powerful influences of divine grace, by the fear of God, and the dread of future punishment strongly and early impressed upon the soul.”

Approximately 90 per cent of the Old Testament and 50 per cent of the New Testament is excluded

He believed that introducing Christianity to enslaved people would make them more obedient and submissive to their masters. He specifically suggested in his letter that clergymen and missionaries should:

“Prepare a short form of public prayers for the them [the enslaved], consisting of a number of the best Collects of the Liturgy, the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and the Ten Commandments, together with select portions of scripture taken principally from the Psalms and Proverbs, the Gospels and the plainest and most practical parts of the Epistles, particularly those which relate to the duties of slaves towards their masters.”

Thus, the Slave Bible was carefully crafted to emphasise doctrines of submission and obedience while excluding passages that might inspire thoughts of freedom or rebellion. The creators of this Bible were acutely aware of the power that religious teachings could have in shaping the minds and hearts of the enslaved population, so sought to manipulate the Christian faith to serve the interests of the colonial rulers and slaveholders. In his letter, Bishop Porteus, a key abolitionist, comes across as a contradictory figure as he presents acutely racist and paternalistic arguments in support of his vision.

Inside the Slave Bible

The most striking feature of the Slave Bible is the extent to which it differs from the traditional Bible. It is not merely a shortened version but a heavily censored one. The Old and New Testaments were drastically edited, with significant portions removed. Approximately 90 per cent of the Old Testament and 50 per cent of the New Testament is excluded.

A pro-slavery ideological agenda is obvious from some of the editorial choices. For instance, it contains the story of Joseph being sold into slavery, but does not have the story of the liberation of the Hebrews from the Egyptians in Exodus. Similarly, passages that speak of equality, justice and God’s wrath against oppressors were excluded.

The selections from Genesis include the first three chapters, which cover the creation of the world and Adam and Eve in Eden but omit chapter four, which tells the story of Cain and Abel and the first murder. The narrative picks up with chapters six to eight, which tell the story of Noah and the flood, but skips chapter eleven, the story of the Tower of Babel and chapter twelve (God’s call to Abraham and God’s promise “in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed”). The only selection from Exodus includes chapters 19-20, Israel’s arrival at Mount Sinai and the delivery of the Ten Commandments to Moses.

Conversely, passages that encouraged submission to authority, such as Ephesians 6:5 (“Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ”), were retained and emphasised. Passages that emphasised equality between groups of people were also excised. This included: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). The Slave Bible also doesn’t contain the Book of Revelation, which tells of a new heaven and earth in which evil will be punished. The goal, it seemed, was to present a version of Christianity that supported the status quo, reinforcing the idea that slavery was divinely ordained and that resistance was against God’s will.

Distribution and usage

The Slave Bible was distributed primarily in the British West Indies, where the demand for control over enslaved Africans was most acute. It was used by missionaries who were tasked with converting slaves to Christianity. These missionaries would often set up schools and churches where they taught reading and religion, using the Slave Bible as a central text.

The distribution of the Slave Bible was closely monitored. It was not a book that was freely available to all. Instead, it was specifically given to enslaved people by those in power, ensuring that the teachings within were controlled and that the enslaved population was exposed only to the parts of the Bible that served the interests of the colonisers.

The underlying purpose of the Slave Bible was to control the spiritual and psychological lives of enslaved Africans

The Bible was used in religious services and education, creating a socio-religious environment that was deeply intertwined with the institution of slavery. In this way, the Slave Bible played a crucial role in the system, serving both as a religious and a political tool.

Colonialism, slavery and Christian mission

The creation and use of the Slave Bible cannot be understood without considering the broader context of colonialism and slavery in the British Empire. During the 18th and 19th centuries, European powers were expanding their empires, and with this expansion came the exploitation of indigenous peoples and the forced labour of enslaved Africans. Christian mission was often tied to these colonial endeavours, with missionaries accompanying colonists to spread Christianity among indigenous populations and enslaved peoples.

The intersection of Christian mission, colonialism and slavery is complex and often contradictory. On one hand, missionaries were genuinely interested in the spiritual wellbeing of the people they sought to convert. On the other hand, their efforts were deeply entangled with the colonial systems that financed them, and oppressed and exploited those very people. The Slave Bible is a stark example of how Christianity was engineered to serve the materialistic and wicked interests of humans. The use of the Slave Bible also highlights the moral contradictions within the Christian mission even today. While many missionaries believe in the spiritual equality of all people, they often operate within systems that deny that very equality. The Slave Bible reflects this tension.

The Slave Bible played a crucial role in the system, serving both as a religious and a political tool

The legacy of the Slave Bible is a painful reminder of how religion can be distorted to serve the interests of power and oppression. It stands as a testament to the ways in which the Christian faith was used to justify and maintain the institution of slavery. It raises important questions about the role and complicity of the Church in Britain, particularly in relation to colonialism and slavery. The Slave Bible also challenges modern Christians to reflect critically on their own faith and its history, calling us to acknowledge the ways in which Christianity has been used to oppress, and to seek a deeper understanding of the true teachings of the Bible. It is a reminder that the message of the Bible is one of liberation, justice and equality, and that any attempt to distort that message must be resisted.

The Slave Bible is available to buy on Amazon here.

References

Bansah, Worlarnyo (2020) ‘Christian Colonialism, Slavery And The African Diaspora’, Noyam, Vol. 6, Issue 2. Available here.

Bishop Porteus Beilby’s letter can be read online here.

Patterson, O. (1982) Slavery and Social Death: A comparative study. Harvard University Press. Available here.

Turner, M. (1982) Slaves and Missionaries: The disintegration of Jamaican slave society, 1787–1834. University of Illinois Press.

Dr Sheila Akomiah-Conteh has a PhD in Divinity from the University of Aberdeen, where she researched the changing landscape of the church in post-Christendom Britain, with a focus on new and emerging churches in Glasgow, Scotland. Sheila is a lecturer in African Theology at Church Mission Society, qualitative research associate at Brendan Research, Edinburgh and a research fellow at the University of Aberdeen. For more information visit missioafricanus.com and brendanresearch.com

Follow her on X (Twitter) @SheilaAkomiah

1 Reader's comment