When the simple Pentecostal faith she inherited cracked under pressure, Dr Selina Stone’s faith evolved into a spacious, generous theology. She spoke with Jane Knoop about how this has changed her life

How would you describe the faith environment you were born in to?

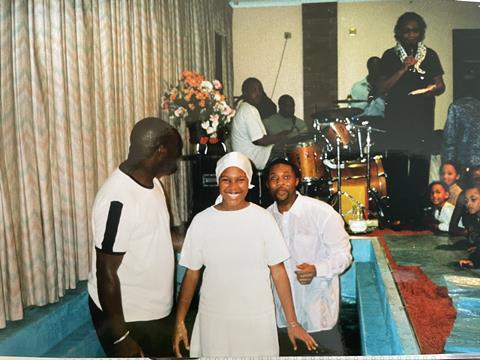

I grew up in a black Pentecostal church in Birmingham. It was a vibrant church experience; charismatic and family oriented. I felt very close to God as a child and grew up as a confident young person in my church, with frequent opportunities to lead and even preach from the age of 14 – I never felt limited by my gender. It was a space where I could be myself, where I felt safe and supported. I was wholeheartedly into my faith and loved the Bible; I would read it every day for my morning devotions and we would read it as a family. I never remember struggling with doubts. Faith in God was as natural to me as breathing.

How has your faith evolved since your childhood?

My faith journey became more complicated during my third year of university. I was studying French and Spanish at Birmingham university, learning about the history of colonialism – including the role of the Church in colonial history. It jarred with the specific perspective of church I’d been presented with growing up: the Church as the hope of the world; a body of people representing faith, justice, truth and righteousness. Learning about the reality of the Church’s history challenged the narrative I’d grown up believing, shaking its simplicity and causing me to question whether the church ‘truth’ I’d signed up to was authentic or relevant in our present-day social and political context.

It’s important for us to be open to other perspectives and to explore and challenge our own

Despite the unchartered territory I found myself in, after graduation I felt called to go to Bible college. Studying theology revealed how simplistic my perspective on the Bible was; I felt compelled to engage with its complexity alongside wrestling with my inherited beliefs and their outworking in the Church. Amidst all this, my mum became ill with cancer. I returned from a mission trip to Northern Ireland where we had witnessed healing on the streets, to find my mum unable to get out of bed. Where was God now that my reading of scripture didn’t match my experience?

All this happened over the course of a couple of years. It marked the start of me thinking critically about what I believed, because – so it turns out – life isn’t as straightforward as we might think.

What do you mean by thinking critically about faith?

Critical thinking is about exploring rather than supressing the questions we have. We cannot comprehend God. Talking about life, God and spirituality requires humility; it’s important for us to be open to other perspectives and to explore and challenge our own. When we make life choices based on something we believe the Bible is saying, it’s important to first question where the idea is coming from.

We can be lured into a culture of faking certainty, when in reality life and faith are complex. When we look at scripture, in my mind at least, we see that Jesus is relaxed about people hanging around him with questions and uncertainty; he’s not anxious or angry about that. He’s not trying to get people to sign up to a list of doctrinal beliefs before they can walk with him. God welcomes our doubt coming hand in hand with faith; I do not think God is anxious if we wander off sometimes.

What are some aspects of faith you have reflected critically on?

Growing up we never talked about the sinfulness of politics, racism, sexism, greed or the exclusion and harm we do to each other. It was all about narrow and polarising topics such as abortion and sex. How did we get here? In the Bible we read so much more about the big collective problems of social life that can do harm to people for generations. We often tolerate those sins very easily (especially when they benefit us) and then target particular individuals or groups who we think are more sinful than everyone else when in reality they are not.

Are there any church traditions that you lean in to now?

I moved away from my Pentecostal roots but I’m also coming back to them again in some ways. As someone who is of Jamaican heritage, I am drawn to Pentecostalism’s black roots and inclusion of African spirituality. It is aligned with my instincts in many ways. I feel at home there culturally. It is a spirituality that enables me to engage with my lived experience and our history. It’s very profound, and there is something missing for me when I’m in a white church.

We can be lured into a culture of faking certainty, when in reality life and faith are complex

That said, I am nourished and moved by the liturgy of a traditional Anglican church service, which allows me to confess and exchange peace with those around me. It grounds me in a Christian identity that doesn’t depend on me working myself up into a worshipful moment.

These days I look for honest, authentic spaces, whether it’s white Anglican, black Pentecostal or a contemplative retreat. I seek spaces that tell the truth about life and its messiness, and allow me to reflect and meet God.

Why do you think it’s important to make theology widely available?

In my mind, the only reason that I’m still able to call myself a Christian is that I’ve been exposed to theology that has helped me to process life, trauma, suffering and grief. A lot of the challenges people deal with in their faith are due to a lack of accessible theology – by this I mean they don’t have different perspectives on the Bible, faith and spirituality to help them navigate life when it gets messy.

I grew up with simple ideas about life, including a belief in a God who would always heal and always provide. I didn’t know how to cope when that didn’t happen. There was no flexibility. I had a rigid faith that broke under pressure. Theological education is about faith and life, and about allowing us to navigate the challenges in our lived experience. I believe theological education allows us to have flexibility and space in our faith so that when pressure comes it can move, shift and absorb, rather than crack.

Dr Selina Stone is a postdoctoral researcher and consultant. You can hear more from her via her podcast ‘Sunday School for Misfits’, or follow her on Twitter @SelinaRStone and on Instagram @selinarstone

No comments yet