While dating is a modern concept, Elaine Storkey unpacks two biblical stories where women were given a voice when deciding their future

Study passages: Genesis 24, Ruth 3–4

I was once asked by a big London church to speak to a gathering of 20-somethings after the evening worship service. The group encouraged Christian believers to get to know each other and grow into greater discipleship, so I prepared a pastoral and spiritual talk. To my surprise, however, during the notices the pastor announced the title of my talk as: ‘What I expect from a date’. I was just about to celebrate my silver wedding, so all my ‘dates’ for the last 25 years had been with my husband (and fairly predictable!) so I felt suddenly out of my depth. For the final ten minutes of the service, I prayed my way out of my nicely prepared talk and listened hard to what God might want me to say.

I remembered conversations I had had with singles at that church, and I hope what I said gave them some freedom from the assumptions and expectations of others – or themselves. But there was no Bible passage I could turn to, because dating is not a biblical concept.

The decisions of these women have had such significance for generations to come

Relationships between women and men were regulated largely by families, conducted on kinship lines with implications for the inheritance of land. The first ‘date’ might be when two families, or their representatives, met to arrange a marriage between a son and a daughter.

‘Courtship’ in Old Testament times

Two Old Testament stories give the flavour of initial encounters between potential spouses. The first one concerns Isaac, the son of Abraham and Sarah, and Rebecca. Having decided it was time for Isaac to marry, his parents set about finding a bride for him. He was to marry someone who worshipped God and shunned idolatry, which was to be an obligatory accepted pattern for the people of Israel. It meant that marriages were inevitably between extended family members, because all the surrounding cultures worshipped idols. In Isaac’s case this involved a long journey back to Abraham and Sarah’s origins.

In the story in Genesis 24, Isaac stayed at home while a servant was given the task of going back to his ancestral home to look for a suitable bride. Of course, he had no authority to choose on his own. Strong indicators of what he should look for were laid down, surrounded by lots of prayer for guidance. When the servant got to the territory of Abraham’s brother, Rebecca was watering the animals. Rebecca’s kindness, warmth, generosity and beauty fitted everything that the servant was told to look for. God confirmed in a sign that she was the woman Isaac should marry (vv40-46). So, the servant was warmly welcomed, family greetings were conveyed, mother and brother were consulted and the promise of marriage made on Isaac’s behalf. But then an issue arose. The servant was keen to begin the return journey quickly but the family wanted to hold on to their beloved Rebecca a bit longer. The question was resolved in a way that went quite against the patriarchal culture, where women’s lives were decided by men. The decision was given to Rebecca; she was allowed the choice of whether or not accept the proposal and go with the servant (v57). She chose to say yes, and the rest is biblical history!

An extraordinary first date

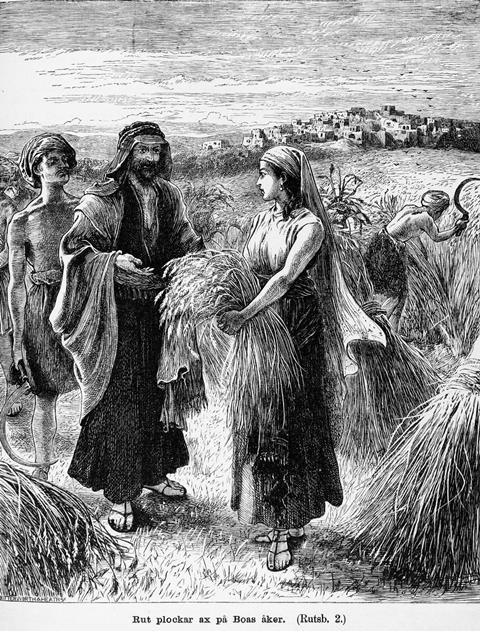

The second story I’ve chosen also has counter-cultural elements. It’s found in the book of Ruth, chapters 3 and 4. Its extra dimension is that the potential bride was not an Israelite. Naomi and her daughter-in-law, Ruth had both been widowed and had returned from Moab to Israel, Naomi’s homeland. Naomi knew that there would be little future for Ruth, a Moabite, unless she secured a Hebrew husband. She had her motherly eye on her kinsman, Boaz, a wealthy, older man whose reputation for kindness and generosity fitted the bill as a good match for Ruth. Yet Naomi’s method for arranging the first date sounds utterly extraordinary to our ears.

Ruth had already met Boaz when she was working in the fields with other women. He noted she was a foreigner who had left her homeland to stay with her deceased husband’s mother Naomi; he blessed her for her kindness and instructed his work officials to make her job easier (Ruth 2:8-12,15-16). But in this public context, there was no way for either Ruth or Naomi to approach him about marriage. So Naomi sent Ruth to uncover Boaz’ feet as he slept among the others. The idea was to wait for him quietly to waken, so she could speak to him when no one else could hear. When he woke, he was stunned to see her lying there, but she got quickly into her request, asking him to cover her with the corner of his robe as her ‘kinsman redeemer’ (Ruth 3:9). It was a ritual that Boaz understood immediately. As the relative of her dead husband, he was being asked to marry his relative’s widow and so fulfil the Hebrew custom of Levirate marriage. Nothing sexual was involved in this interchange, just an implicit request. His response was to be very flattered that she had chosen him over younger men and promised to sort it out with the closer male relative who had greater kinsman claim (vv10-12). He invited her to sleep the night out there, but to slip away before others awoke. Naomi’s plan worked to perfection; Boaz made the arrangements with his other relative, then married Ruth (Ruth 4).

Given her say

These stories are remarkable, not because they defy the traditional customs; they don’t. They are unusual in that in each case the young woman was given the right to have her say, and her choice was respected. In the case of Rebecca, the future lines of Israel and Judah hung on her decision. In the case of Ruth, her willingness to follow the guidance of her mother-in-law eventually led to the line of King David and culminated in the birth of Jesus. The fact that the decisions of these women have had such significance for generations to come is evidence that God includes women – even a Moabite woman – in his plan for his people.

We don’t find stories like these in the New Testament. There, almost no reference is given to traditional patterns of in-family courtships. The focus is on the ‘household of faith’. Advice on proper behaviour towards a fiancée (a ‘betrothed’) is given to men, but St Paul also directly addressed women (1 Corinthians 7), taking it for granted that women were able to make meaningful choices. Paul also put more emphasis on singleness than in the Hebrew scriptures, to free people up to serve God more wholeheartedly. Yet, three underlying principles remain the same. Courtship is to take place between God-worshipping believers; full bodily expression of sexuality is restricted to marriage; and women have ‘rights’ in marriage relationships that are equal to men (1 Corinthians 7).

How do we interpret biblical patterns in our dating and relationships today?

Dating is a very modern invention. In cultures throughout history, and still in many today, relationships between the sexes were regulated by families and cultural mores. In some contexts, couples rarely spent time alone together until after the wedding ceremony. In other societies, where more freedom was given to women and men to choose their own partners, women would still be chaperoned on any ‘dates’ they went on. I was amused to read an 1881 English upper-class social manual for young women which pointed out: “With the chaperone of course rests the decision as to what parties are to be attended or what acquaintances made” (Glass of Fashion, 1881).

Today, we live in a permissive culture where many people date multiple partners and dating often includes having sex. Sometimes this is because the two have become emotionally involved with each other, but for others sex is seen almost as a leisure activity. The rise of ‘friends with benefits’ now blurs the distinction between friendship and sexual involvement, with sexually transmitted infections continuing to rise rapidly (26 per cent increase in the last year among people aged 16–24). Cohabitation is commonplace before, and sometimes instead of, marriage. Yet social and cultural studies increasingly point to the long-term negative impacts of these patterns of relationships. People with multiple pre-marital partners have the highest divorce rates and cohabitation is less stable than marriage. By the time children turn five, 53 per cent of those with cohabiting parents will have experienced their parents’ breakup, compared with 15 per cent of children of married parents.

So how should Christians approach dating? Most of all dating offers a time for getting to know someone, assessing their values and personality and exploring what you have in common. It’s a process for growing a friendship, learning how to love and encouraging faith in another person’s heart. Wonderfully, today’s culture does give us these freedoms. When Christians can bring their relationship to God in prayer, sharing their dilemmas and asking how to express love appropriately they find the blessing of knowing God is in this relationship too, and can be trusted with the future.

No comments yet