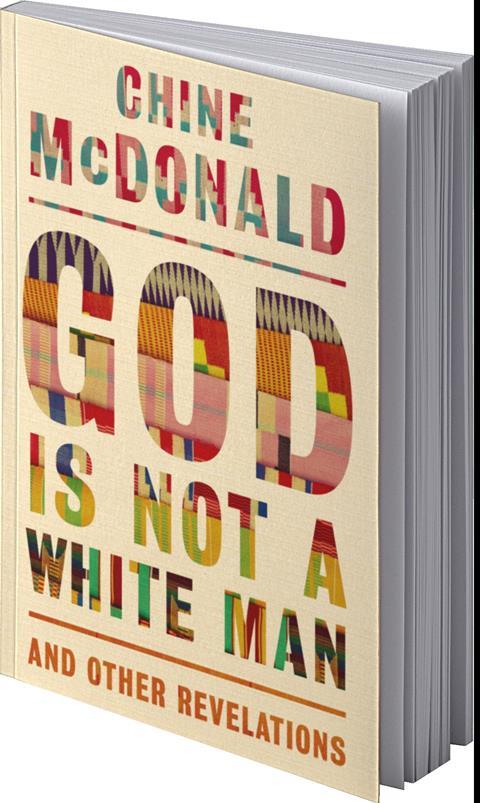

Author Chine McDonald spoke to Rachel Pearce about her new book, God Is Not A White Man: And Other Revelations

“I bet you’re not used to this kind of food at home.” This comment from a mature white lecturer came as something of a surprise during the first grand dinner Chine McDonald attended as a theology student at Cambridge University. Chine may have lived in Nigeria until she was four, but chicken and potatoes weren’t exactly radical fare.

“There are various points in my life where I’ve had these kinds of revelations of: ‘Oh, I’m not like everyone else, or I’m not seen as being like everyone else. I’m treated differently,’” she explains.

A lifetime of microaggressions

Chine, who is currently head of community fundraising and public engagement at Christian Aid, describes incidents like this as ‘microaggressions’.

When she was a youngster, her family turned up at a new church in Herefordshire to be asked by the woman on the welcome team: “What made you choose this church rather than the black church down the road?” Some of the churches she attended as a child hosted International Sundays as an attempt at diversity and inclusion. “The immigrant communities would wear clothes and bring food from their home countries, but white people wouldn’t have a thing. The default is white British, and everything else is different and other.”

Later, while speaking about race and faith to a church congregation of mainly older white people, Chine was a little baffled when a hand went up and the person said: “If I was listening to you on the phone, I wouldn’t even know you were coloured.”

“I feel like some people take that idea of ‘colour-blindness’ – oh, you’re just like one of us – and try to pass it off as a compliment, when really what they’re really saying is that blackness or being from an African country is in some way inferior,” she says.

When white masculinity is the ultimate prize

Chine’s new book, God Is Not A White Man: And Other Revelations (Hodder & Stoughton), was written to give a black British, female, Christian perspective on issues of race, racial justice and theology.

“One of the consequences of a world that sees whiteness and maleness as superior is depicting God as both white and male, although we know that Jesus was a brown man from the Middle East. We know that God is not white or male; God is completely other. So I used that as a lens through which to explore what it means to be black and female, as in the opposite of what is prized as superior – inside and outside the Church.”

Chine chose to interchange the terms ‘white supremacy’ and ‘white superiority’ in the book because people often associate white supremacy with the Ku Klux Klan, with using the ‘N’ word, or with violence, racism and hate crime. “A lot of people do not see themselves as racist because they don’t do those things. But I have tried to show that white supremacy and white superiority are pervasive – there is an underlying sense that whiteness is best.

“Even though people might not consciously think that, if you go to most churches on a Sunday morning, you’re likely to see white people leading the service, hear white theologians being quoted in sermons and you’re likely to sing songs written by white people. We believe that God created all of us equally, but that doesn’t really play out in churches.”

No level playing field

Many Brits see institutional racism as an American problem. After all, George Floyd was killed on the other side of the Atlantic, wasn’t he? And shouldn’t we, as Christians, be concerned about ‘all lives’ rather than just ‘black lives’?

According to Chine, the issue is that the playing field is far from level for black people, particularly women, in what she describes as a “world made for white men”. “If you want to know about institutional racism, ask any black person who walks outside their door or goes into a shop in any part of the UK,” says Chine. “Institutional racism is difficult to see, because it’s so baked into our systems.” A quick glance at statistics relating to the rate at which black people are imprisoned or at which black mothers die in childbirth makes this abundantly clear.

“I think it’s really easy for us to look at the US and think: ‘Well, they’re much more extreme. George Floyd was killed in the street by a police officer.’ But we forget that there are lots of instances of violence against black people who are incarcerated in UK prisons. And there are many examples of young black people who have been killed for the colour of their skin, like Stephen Lawrence and Damilola Taylor. It’s definitely not just an American thing.”

Forming friendships

Chine’s aim in writing on this emotive subject was to help white Christians understand the ways in which black Christians feel ‘less than’ in society and in Church. Her desire is for people to listen and respond to the experiences she documents rather than arguing over terms like ‘white supremacy’ and ‘black lives matter’.

“I hope it enables people to see the world through someone else’s eyes and challenges white superiority, but also any sense of black people being ‘less than’. The point and the beauty of sharing these stories is that we form relationship with each other.”

She also feels it would be beneficial for white people to create spaces among themselves to talk about race: “There needs to be some kind of follow-up in order for it to have an impact,” she says.

Silence isn’t an option

The book makes it clear that we need to be anti-racist if real change is to occur, but how do white people engage in meaningful conversations without being accused of either being racist or ‘woke’?

“It’s a tricky balance, but silence isn’t an option. It’s about not just sitting back and letting racism happen. It’s about challenging it where you see it. Anti-racism is an active term; it’s about doing. It’s proactive rather than passive. It’s recognising that there are tangible things we can do to address racial injustice in our midst.”