‘I realised that Christianity had a history that included women beyond the Bible stories. As a girl growing up in a traditional parish where women did not participate in any ministries, this was transformative,’ says Nancy Walbank.

“Why isn’t Easter on the same date each year, like Christmas?” I asked my mum when I was ten years old as I tried to understand why my birthday had fallen on Ash Wednesday. Fasting and abstinence were not how I wanted to celebrate my tenth birthday! Mum explained that the date of Easter had been agreed at the Synod of Whitby, and a lady named Hild had brought together different groups to agree on a formula for calculating Easter Day.

READ MORE: We don’t have to understand everything that happened at Easter

Immediately, I wanted to know more about this woman. We were a large Catholic family living in a small town. As far as I knew, the parish priest oversaw everything related to religion. My only notion of Church hierarchy was an oil painting of Pope Paul VI that hung on the living room wall, and his eyes followed you around the room. It was a raffle prize.

The idea that the decision about Easter had been made in Yorkshire and by a woman was a revelation. I wanted to know more.

The idea that the decision about Easter had been made in Yorkshire and by a woman was a revelation. I wanted to know more. Mum directed me to go and look at Butler’s Lives of the Saints in a cupboard upstairs. Butler’s was four green leather books with tarnished gold crosses on the front. They smelled terrible, and the pages were spotted with age, but I found an entry about a Saint Hilda, Abbess. It was a difficult book to read.

I learned that Hilda came from a royal family and had chosen to be a nun. She had established monasteries at places I couldn’t pronounce and at Whitby. Saint Hilda was the Hild mum had told me about. The book seemed to focus on the men around her and the battles they fought but did say that Hilda had a talent for reconciling differences.

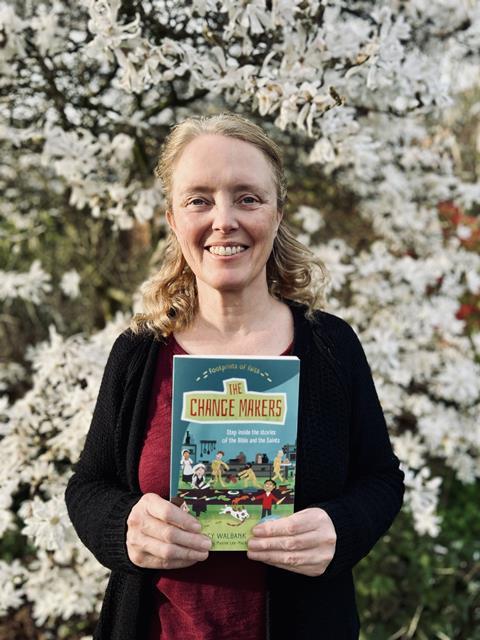

On that day, I realised that Christianity had a history that included women beyond the Bible stories. As a girl growing up in a traditional parish where women did not participate in any ministries, this was transformative. When I started to write The Change Makers, I knew Hild had to be a saint I featured so children could hear her story and know that sometimes big decisions about British Christianity are shaped by women in Yorkshire.

READ MORE: ‘I am a Palestinian Christian and will be retracing the steps of Jesus to find hope this Easter’

Learning about Hild as a ten-year-old began a process of understanding Christianity as a lived religion, passed on through generations, shaping people’s lives, the buildings and the landscape. Ultimately, this path led me to work as an RE adviser, where I was tasked with developing a programme of study for Catholic primary schools on understanding virtues. Rather than talk about virtues as abstract habits, I wanted to illustrate what it meant to live a virtuous life with relatable stories so children could imagine standing in that person’s shoes, making choices and decisions.

“The problem I’m having,” I complained to Darcy, my parish deacon, “Is finding a saint the children can relate to that connects with social justice issues today.”

READ MORE: Easter with Wintershall: Taking Jesus’ story to where people are

Darcy thought for a moment and then suggested Josephine Bakhita. I admitted I’d never heard of her, so he found an information leaflet. Just like the children in The Change Makers, I felt incredulous that I had never heard Bakhita’s name. Here was a story that would speak to the children. Trafficked as a seven-year-old from her village in modern-day Sudan and forced to work in domestic service, Bakhita was so traumatised that she forgot her name. The people who enslaved her gave her the nickname Bakhita, meaning lucky. Impossible as it seems, Josephine Bakhita later felt that this was true. Her suffering ultimately brought her to know Christ and experience freedom following the intervention of an Italian court in 1889, after the family who enslaved her returned to Italy.

Josephine Bakhita’s story would challenge children to think about her ability to forgive the people who had enslaved her, forced her to work, mistreated her and not recognised her humanity. In learning about Josephine Bakhita to teach children, her story also challenged me to ask what forgiveness looks like in my life. Forgiveness does not mean others should not be held accountable for their actions, but it does mean letting go of the grudge, the desire to ‘get even’. In The Change Makers, the children encounter her story beside the sculpture by Timothy P. Schmalz, which I saw in Rome, as people stood around asking what the sculpture was all about. I hope that in reading her story, children can explain how Josephine Bakhita lived out the virtue of forgiveness in her life.

When I started to plan The Change Makers, I had to choose five saints to feature. I wanted to find stories that would connect with children, whatever their religious background because the person they encountered had lived an extraordinary life. I thought the best place to start was to think of stories of saints that had changed me. The first two that came into my mind were Saint Hild of Whitby and Saint Josephine Bakhita. In writing the stories for children, I’ve reconnected with my discovery of their remarkable lives.

No comments yet