Writer Jo Acharya experimented with ChatGPT and felt uncomfortable, not by the level of intelligence it displayed… but the level of “imagination”.

In the beginning, God created. He spoke into being, blessed his handiwork and called it good. Then he formed the first humans, breathing his life into their lungs and saturating them with his own image. Like him, we are creative beings, bursting with imagination and ingenuity.

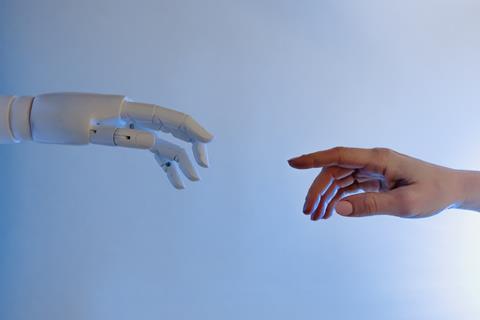

It’s human ingenuity, of course, that lies behind recent advances in artificial intelligence. The Lensa app has been causing a stir with its digital portraits, which show users in a range of artistic styles. And ChatGPT has burst onto the scene boasting a remarkable ability to answer questions, complete professional tasks and even compose poetry.

There are many ethical questions around the use of AI technology, but what worries me is the threat it poses to human creativity. Lensa was “trained” on the work of human artists without those artists’ consent, enabling it to copy their individual styles. Many of the artists involved have spoken out, calling this practice theft. ChatGPT has also been trained, this time on reams of data from a diverse range of sources. Based on its learning, it can generate any kind of writing the user requests – with varying results.

I got ChatGPT to write a decent poem about a sunset, with nice use of adjectives and metaphors.

When I tried ChatGPT, I was impressed and concerned in equal measure. It’s very good at what it does, responding to critique and refining its output based on a user’s instructions. With a clear brief and a few rounds of suggested edits, I got it to write a decent poem about a sunset, with nice use of adjectives and metaphors. If I didn’t know better, I might even say imagination.

That’s what makes me uncomfortable. This technology will only get better, and it’s not hard to picture a future where AI programs could produce new literature, art and even music far more cheaply and efficiently than people. It is already difficult to make a living in the arts. Could human creativity survive in an industry dominated by profitable imitations?

There are philosophical questions for the rest of us too. If you can’t tell that your favourite novel was written by an AI, does it really matter? I think it does. It’s the image of God in us that inspires us to create. Like him, we put something of ourselves into everything we make. Human personality, emotion and intention are intrinsic to creative work; they can’t be sacrificed without losing what makes it precious.

It’s the image of God in us that inspires us to create. Like him, we put something of ourselves into everything we make.

The Russian composer Igor Stravinsky once said: “Only God can create. I make music from music.” A human artist forms and arranges what God has already created. AI reforms and rearranges what humans have made. The result is generated without understanding, stripped of both divine spark and human intention. It may be superficially similar, but it is no substitute for the real thing.

Artificial intelligence is here to stay, and many of its applications will be truly beneficial. But if we are concerned about protecting human creativity, we must value it by choosing depth and originality over efficiency. Let’s honour art that reveals the heart of a real person. And when human creativity delights us, may it draw us toward the author of creation in worship. This, after all, is what we are made for. Ephesians 2:10 tells us that we ourselves are God’s handiwork, living masterpieces called to reflect his wonderful imagination and love into this world.

No comments yet