Nigerian-born comedian Joy Carter was abandoned at birth, lost her twin and then raised by a white British couple. She spoke with Alex Noel about infant trauma and learning to navigate the sexist and racist world of comedy

Joy Carter’s comedy credentials have earned her award nominations and plaudits from fellow comedians, TV personalities and broadcasters. But her beginnings were no laughing matter. Joy was born into the Biafran War (the civil war that devastated western Nigeria in the late 1960s). She was found, together with her twin sister, by a Save the Children nurse: “She found two [abandoned] babies. One was dead. One was alive – she picked me up and took me to the local hospital.” Because of the war and lack of any records, there was no information about Joy whatsoever, not even a name.

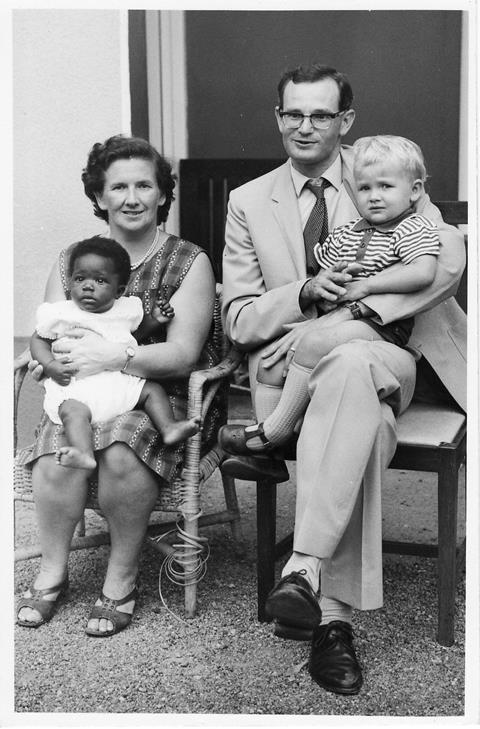

It was her adoptive parents who named her Joy. Originally from the UK, they had met and married while working as missionaries and decided to join the relief effort when the war broke out. Arriving at the hospital with their young son, they asked what they could do to help. “Look after a baby”, they were told – the hospital was inundated and couldn’t cope. The nurses gave them Joy. It didn’t take long for them to make up their minds: “My dad said: ‘We feel we should [adopt this baby].’” The nurses had warned him: “‘Don’t pick that [one] because she’s dying of pneumonia’”, but he was undeterred: “My dad said: ‘Even if we only have this baby for three weeks, we think her life is worth it.’”

Navigating the thorny issues

Joy describes the importance of having people around her who are there for her: “That’s one of my big tips in this career…you need the right friends.” Without them she admits that: “psychologically, it could break you”. In difficult situations or where she’s been mistreated, she’s learned: “there’s a justice that only [God] can bring, and he will recompense you…that’s a great peace [to have] in this industry”.

As a black female comic, this is said from experience: “Comedy is a bit like politics…it’s still a really strong bastion of sexism and racism.” She refers to a YouGov poll that lists the most well-known British comedians. Alan Carr and Ricky Gervais top the list, with Jo Brand and Dawn French the only two women inside the top ten. Lenny Henry is the first black man to feature at number 19. “So where’s the first black woman?!”, she asks rhetorically. It’s Elsa Majimbo at number 83.

“[Comedy is] still a male-dominated area,” she explains, “and when it comes to ethnicity and diversity it’s still really, really bad…you switch on the television, and you ask yourself first of all, ‘Where are the women?’ then ‘Where are the black women?’”

My dad said: ‘Even if we only have this baby for three weeks, we think her life is worth it’

She’s conscious of the pitfalls and responsibilities of fame: “OK, have a great career. But what did you do to love people? How were you off set? Did you make people tea? Jesus came to serve, not be served, and those [doing that] are the real celebrities.” Her own role models include Maya Angelou: “that’s what I call a real icon”.

So, which comedians does Joy admire? “One of my [favourites] is Lucille Ball…she just did what she did, she just made comedy. I also love London Hughes.” As a comedian, embracing yourself is vital: “You’ve got to come to the point where you own your personality.” She observes that: “it’s still very, very tricky for female comics”, especially in the UK where competition is rife: “You could maybe scrape a living before lockdown…but now [our] little pool has become like soggy mud and everyone’s flapping [about], even the top comedians.”

The situation is not helped by those who control, and even limit the opportunities to perform, including promoters. But Joy won’t be put off: “I’ve spent my lifetime trying to fit into a box I would never, ever fit into. It’s like chasing after the wind…I just felt the Lord say, ‘Joy, you’ve got to become the change, and you’ve got to become [who] I say you are.’”

This has been a game changer: “I don’t need to hustle [or] push anymore.” It influences how she prepares for her shows too: “I’m trying to be really intentional and frame up the gig before I even get there. I want the angels to come, I want [God’s] power to move…I want to see people who come to my gig literally laugh themselves well.”

Trauma and joy

Performing for an audience full of women at a Salvation Army conference was a case in point: “A lot of them [were in] domestic violence situations or [had] immigration issues, or [had] nowhere to live…300 traumatised ladies. They put me on in the afternoon…I mean, it was electric. After the show, women were saying to me, ‘I’ve not laughed for 20 years.’”

In preparing for that gig, she shares: “God told me to get all the ladies to wear party clothes.” On the day itself, those who wanted to were invited to dress up – putting on purple wigs, mermaid outfits, silly glasses, unicorn hats or Stetsons. It added an extra dimension to the sense of laughter and hilarity. “It’s funny…and God is teaching me to understand the realms of joy”, she says. Psychological research suggests that while trauma can severely dampen one’s capacity to experience joy, making time to be joyful can actually rewire the brain, and help to bring healing.

As a black child adopted into a white family Joy struggled to find a coherent sense of identity

Joy herself was traumatised by her earliest experiences. As a young child she was mute: “I sort of shut down. My mum was very kind, she said: ‘Joy, even if you don’t want to speak to us, you can speak to our cat Tigger, and he’ll tell us.’ So my mum gave me a beautiful outlet [and] permission to not want to speak.” Despite having little knowledge of trauma or PTSD at the time, Joy’s parents found a way to meet her needs. She encourages others to do the same: “If you’re looking after children who are very challenging, love will find a way.”

Empowering others

In 2014 Joy founded Adoption Arena: “to empower the adoptive community…not just focus on the trauma”. It provides resources for adoptees, foster families and carers, and her podcast (launched during COVID) discusses the issues faced – such as transracial adoption: “My family did really well. I was just Joy, who was their daughter.” Still, as a black child adopted into a white family she struggled to find a coherent sense of identity, further compounded by the racist bullying she experienced at her school in Scunthorpe, being the only black pupil. She developed anorexia as a result of compounded trauma. She even questioned her reason for living: “It was a very difficult time; I had to really think: ‘Do I still even wanna be here?’ But I saw the loving kindness of God. He was just so gentle and kind, and we talked through why I should be here.”

She is eager for others to find their healing, both individually and generationally. Being able to accept her name as God-given was a key moment: “I hated being called Joy but now I love it…Once you stop fighting and embrace who God says you are, then you start to flourish [because] you’re agreeing with what God says.”

Her new show ‘Joy on Joy’, tells her story of adoption and is centred around the power of joy: “It’s what God will give us when all our hopes have been destroyed. And that’s one thing that I know is true of my life.” Being a comedian is a serious calling: “We have to remember; in the dark days, especially if you’ve got a long-term illness [or other] darkness that you’ve got to walk through with the Lord, how to operate in joy…God will give you joy every day if you ask him.” If that’s not possible to begin with, Joy has a suggestion: “watch a cat video…hilarious”.

Learn about Joy’s comedy, career and advocacy work at joycarter.co.uk and for Adoption Arena visit adoptionarena.com

Listen to Joy’s conversation with Carlton Baxter for Premier Radio in support of Adoption Week here

No comments yet