Whatever happened to the good news?

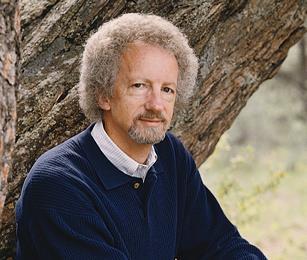

Known for his honest and thoughtful explorations of faith amidst struggles and doubts, Philip Yancey talks to Claire Musters about the themes in his new book Vanishing Grace

Too many people view Christians as bearers of bad rather than good news

One reason is that the Church has made some terrible mistakes over the years (the Crusades and the Inquisition etc). In my country, the US, non-religious people associate faith with the prefix “anti-” – anti-abortion, anti-pornography, anti-homosexual rights – perceiving Christians as a kind of morals police. And, let’s be frank, people rebel against whatever deprives them of the ‘right’ to fulfil their own desires.

I think we need to reclaim the ‘goodnewsness’ of the Gospel

And the best place to start is to rediscover the good news ourselves. If you had asked me 20 years ago about the word sin, I might have said something like, “God’s Word for keeping us from having a good time.” Now I would say, “God’s word for keeping us from harming ourselves.” In Western countries the top 10 health problems are all things that we do to ourselves. We drink too much, eat too much, have sex with the wrong people and take too many drugs. Addiction is the culturally acceptable word for the results of sin. It took me years to realise that God desires the very best life for us on earth. While researching this book, I took pains to explore for myself the goodnewsness of the Gospel – something I missed growing up in a strict church environment.

We should always look for those golden opportunities to dispense grace

So many times I fixate on efficiency, deadlines and my own selfish concerns. I go to the supermarket and get irritated at a clerk who keeps me waiting. I snap at the Filipino on the end of the computer helpline when I have trouble understanding his English. I treat a receptionist like a machine, not a person. Our modern technological age seems to encourage that treatment. I have to consciously slow down, pay attention and ask God to point out times when I can bring a note of grace into someone else’s life.

Sceptics and post-Christians need a dose of grace too

To the performance-based, unforgiving, harsh and competitive world that surrounds them, Jesus’ followers have the opportunity to show another way to live. We care for the vulnerable not because of what they might do for us, but because we are expressing God’s love for “the least of these”. When wronged, we respond not with revenge but with forgiveness, as God has treated us. In so many ways we can represent grace to a world that runs by what I call “ungrace”.

Too easily we expect God to do something for us when instead God wants to do it through us

I tell the story of Bono, who spent six weeks with his wife at an orphanage in Ethiopia. When he returned, his prayers had changed. “God, don’t you care about those children – there may soon be 15 million orphans in Africa because of AIDS!” Eventually he heard the (at first unwelcome) answer that, yes, God cares, and in fact had chosen Bono himself to express that care by leading a campaign against AIDS. Our prayers are like boomerangs: we toss them at God, sometimes in confusion and rage, only to find them looping back to us. For whatever reason, God has chosen ordinary human beings as the conduit for expressing his will on this planet.

For true dialogue to occur, we must cut through stereotypes and genuinely consider the other’s point of view Perhaps this is part of what Jesus meant when he said, “Love your neighbour as yourself”. Christians sometimes have the reputation of marketers: we see non-believers as targets. Our goal is to convert them, to get them to accept our beliefs. I’m touched by the scene of the rich young ruler who came to Jesus, listened to him and walked away unable to accept Jesus’ message. Mark adds, “And Jesus loved him”. Jesus never asked us to clean up the world or to convert every single person. We are asked to demonstrate the grace of God, which means viewing the other as someone to love and care for.

There is a time to critique the surrounding culture and a time to listen

I’ve learned to look for ‘hinge moments’ when a latent thirst might become evident. Marriage, the birth of a child, illness, death – all of these represent times when people are emotionally pressed and challenged, and look for some sort of deeper meaning apart from the everyday concerns of life. Think of Jesus speaking with the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4). She kept bringing up mundane issues, such as the proper place to worship. Jesus homed in on her underlying thirst, so evident in her history of five failed marriages.

Fear abounds on both sides

It’s as if Christians and the uncommitted are standing across a divide, with both groups fearing each other. The world sees Christians as a threat, intent on enforcing their own rules. On the other side, Christians see themselves as a harassed minority holding out against hostile forces. How do we cross the divide? Well, that’s the whole topic of my book!

+ Vanishing Grace by Philip Yancey is published by Hodder & Stoughton