Over the past five days, we have seen a guilty verdict for Derek Chauvin – the police officer who killed George Floyd; an explosive BBC Panorama documentary Is the Church racist? in which black and brown Anglicans shared their first-hand experiences of institutional racism in the Church of England – which this week released a report by its anti-racism taskforce; the War Graves Commission apologising for the unequal commemoration of black and Asian soldiers during World War One.

Yesterday was also Stephen Lawrence Day, marking 28 years since the black teenager was killed in south-east London.

The role of women

One of the things that has struck me over this week is the role that women have played in some of these stories.

A woman – Dr Sanjee Perera – is the Archbishops’ Adviser on Minority Ethnic Anglican Concerns – and has been a key role in leading the Church of England forward through the anti-racism taskforce and its report From Lament to Action.

The conviction of George Floyd’s killer Derek Chauvin would likely not have been possible without the bravery of a young woman – Darnella Frazier. The 17-year-old filmed the footage of the tragic incident last May, which sparked global Black Lives Matter protests the likes of which we had not seen before. It also led to the firing of three other officers at the scene, as well as a ban on police chokeholds.

One of the most chilling facts about the George Floyd case was that fact that for much of the 9 minutes and 29 seconds that Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck, he was crying out for his mother.

I have often been struck by the heartbreak that black mothers -–whose children have been murdered just for being black – must face. This, of course, includes Doreen Lawrence, who fought tirelessly for decades for justice for her son Stephen.

The pain of black women

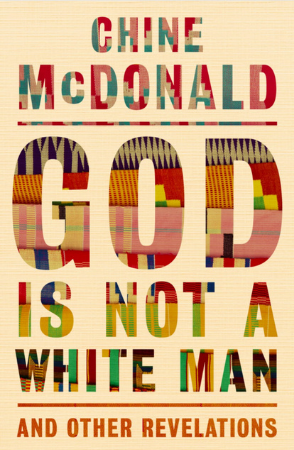

In my upcoming book God Is Not a White Man & Other Revelations (Hodder & Stoughton), I write about the story of black women as told through Beyoncé’s visual album Lemonade, which is rich in theology and imagery and activism.

All black women – even Beyoncé – carry with us the pain of injustices that have gone before us. But life also brings us joy and love and hope. It lays out the texture and complexity of black women’s lives and includes real-life black women in the story.

The short film that accompanies the album features moving scenes of black mothers whose unarmed sons had been killed. Mothers Lesley McSpadden-Head, Sybrina Fulton, Wanda Johnson and Gwen Carr sit for portraits holding pictures of their sons whose names will forever be linked with their deaths: Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant and Eric Garner.

And this week I have been reminded of another black mother who faced a horrific tragedy, who chose to take radical action for racial justice in the hopes of a better future for other people’s sons and daughters.

Mamie Till-Mobley was the mother of Emmett Till, who was killed in 1955 when he was just 14, for allegedly flirting with a white woman (although the white woman in question confessed at the end of her life that she had made the whole thing up). Emmett was brutally murdered by three of the woman’s male relatives.

When making arrangements for his funeral, Mamie Till-Mobley decided to have an open casket in the hopes that when the world saw the brutal violence committed against her son, that it would shake them out of slumber and inaction on racial justice. “Let the people see what they did to my boy.”

Women are often the witnesses to brutality, but we cannot forget that they are also the victims. Women the world over face sexual abuse and violence, and sometimes the names of black women killed by police are forgotten, including Breonna Taylor and Sandra Bland. Black women often face the double threat of violence due to both their race and their gender.

There was rightly an outpouring of grief when Sarah Everard was murdered earlier this year, but there had been little coverage about similar violations against black women.

Wilhelmina Smallman, who was the UK’s first female Church of England Archdeacon from a minority ethnic background, made this point recently.

Her two daughters Nicole Smallman, 27, and Biba Henry, 46, were stabbed to death last June as they celebrated a birthday in Wembley.

Two police officers who were supposed to be guarding the murder scene were arrested after allegedly taking photos of the sisters’ bodies and sharing the images.

In an interview with the BBC, Ms Smallman said: “I think the notion of ‘all people matter’ is absolutely right but it is not true. Other people have more kudos in this world than people of colour so from my point of view, all women, women of colour, white women, all of us we are on the same journey. We are on a journey to say that we all matter.”

Chine McDonald is a writer, broadcaster and author of God Is Not a White Man & Other Revelations (publishing 27 May, Hodder & Stoughton). It’s available to pre-order now.