Hosted by Claire Musters

This month I’m reading…

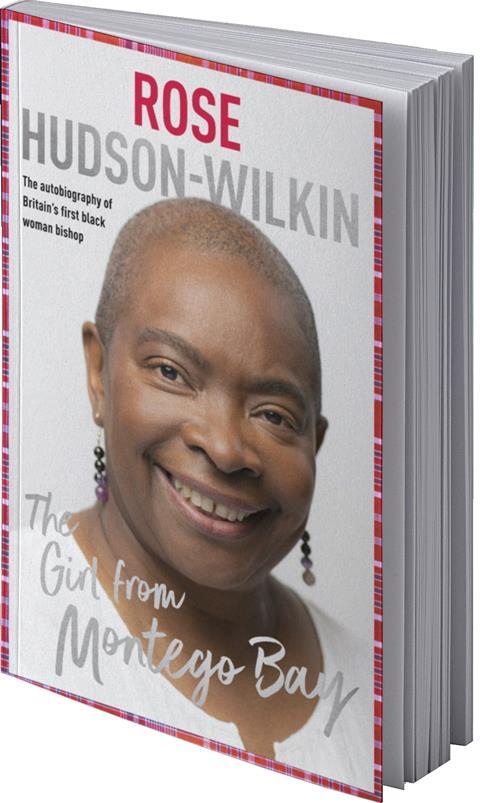

The Girl From Montego Bay: The autobiography of Britain’s first black woman bishop

By Rose Hudson-Wilkin (978-0281089604, SPCK)

Bishop Rose Hudson-Wilkin MBE starts her autobiography describing the moments she met her two heroes: Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela. Attracted to them because she: “loved their resilience, their hope, their way of living out the Christian faith, their uncompromising stance on justice,” she goes on to comment: “Most of all, I loved that they looked just like me!” But she hadn’t wanted to simply meet them; she wanted to emulate them.

Originally from Jamaica, born to parents who simply didn’t know how to parent, from an early age she felt a calling to leadership, which eventually led her to train as an evangelist at the Church Army College in London (Church Army is an evangelistic and mission organisation founded in association with the Church of England), where she also met her future husband, Ken. The book then charts how they navigated life so that both their ministries could flourish.

Rose does not flinch back from describing the many times she was discriminated against due to her colour and her gender, and the pressure she has felt as she has forged the way for others: “I’m conscious of carrying the weight of the knowledge that I am a woman, and a black woman; I don’t have the option of being second best or mediocre, because other black women need to come after me, and how I perform will determine how they are received.” How she ‘performed’ is revealed by the fact that she became one of the first women to be ordained as a priest, the first black priest to be chaplain to the Queen and to the Speaker of the House of Commons, and the first black woman to be a bishop in the Church of England.

The book reads as a series of reminiscences back over her life from the early days up until recently. It isn’t particularly polished, but it is honest – and inspiring.

You were just 14 when you first preached. Could you describe what that experience was like, and how you began to recognise a call to ministry?

From these early involvements, it was agreed that we would experiment in doing this kind of worship at a deanery level (a wider geographical area so not just a parish). This meant meeting with other youth leaders from other parishes to plan the service. When it came to the preaching, I cannot recall how it came about, but it fell to me. On the day it was a very daunting experience, especially as I climbed the steps into the pulpit. I was nervous, but I had prepared well and so knew that I need not be afraid. Using the lectionary, I had chosen the Psalm allocated for the day – Psalm 8 – and focused in on the verse: “What is man that thou art mindful of him” (v4, KJV) .The relief when so many people shared with me how helpful they found my sermon. My young collaborators congratulated me and assured me that I needed to be ready for the next occasion! In my heart, a call to ministry was beginning to stir.

At this young age you asked the bishop how, when women were so much a part of making things happen in church, they weren’t allowed to give Holy Communion. How did you respond when he said: “We are Anglicans. We don’t do that”?

Something inside me said: “His response cannot be the end of this conversation.” I saw the need, I remembered the words from Isaiah 6, “Whom shall I send. And who will go for us?” Like the prophet Isaiah, I too wanted to say, “Here I am! Send me” (v8). As a young girl, I was brought up not to be rude to an adult. Pressing home one’s point would be deemed as rude. So, I kept it all in my heart. Moving to another denomination never occurred to me. This was the place that God called me to be, the context I was baptised in. I was and am a firm believer that God has a plan and knows what he is doing.

It was while training at the West Midlands Ministerial Training Course that you were offered contextual and black theology – what did that mean to you?

British missionaries went abroad, but they did not just preach the gospel – they preached it wrapped in their English culture! Learning that God speaks through the black cultural experience was an eye opener. So enslaved leaders, for example, were able to use the Bible to challenge slavery. Learning from and acknowledging that black people’s interpretation of the gospel was equally valid was most liberating.

The Synod agreed to allow women to be ordained as priests in 1992 – could you comment on the disparity of responses and how you felt about the decision in hindsight?

As a church, we have said that there are no theological reasons why women should not be ordained as priests and consecrated as bishops. On the same page, we say: “Oh a few people have theological objections to it.” Then as a church we have indeed institutionalised the discrimination by creating a parallel structure for those who do not wish to receive the ministry of women. We say we are doing it in the name of unity. But this is not realistic, this is not unity. Women are made to pay the price! In the light of this, the church should have waited until it was ready to give an overwhelming yes. We followed all the right procedures in getting a two thirds majority in the general synod, but still ended up creating this alternative structure because we did not like the outcome.

You were asked to be chaplain to the Queen and then were part of the coronation service for King Charles III – what has it been like to serve royalty?

Thankfully, I saw and respected Her late Majesty, firstly as a woman, a mother, grandmother, wife and then Queen. I did feel a sense of awe, however, to be one of five people taking Holy Communion on the day of the coronation (the archbishop, the bishop of Chelmsford, myself, King Charles III and Queen Camilla). I was part of history in the making.

Your journey towards the role of chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons was far from straightforward. One newspaper highlighted not your credentials but that you were ‘the girl from Montego Bay’ – why did you determine then that if you ever wrote your autobiography that is what you would call it?

In the Old Testament story of Joseph, he told his brothers that when they sold him into slavery, they meant him harm, but that God used it for good. The person who wrote the article used the phrase in a dismissive and disrespectful way. It was their way of saying how could this girl from Montego Bay be compared to having an Oxford graduate [in the position]. However, I am indeed lucky to be from Montego Bay. I determined I was going to use it for good!

You had made history with many of your previous appointments, but how did it feel the day you became the first black woman bishop in the Church of England?

It was a deep joy and a privilege to be called to serve the people of Canterbury diocese as their bishop. I sit lightly with the ‘first’ because it means that it is not normal. I long for it to be normal.

Bishop Rose Hudson-Wilkin on: The books that have changed my life

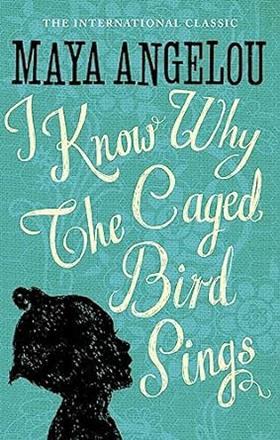

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

I read this book when I was about 13 years old. It immediately spoke to me. Her story was my story. She did not just survive, she thrived. I carried the hope from this.

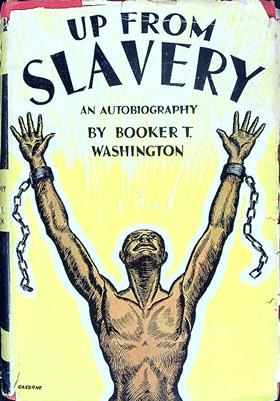

Up from Slavery by Booker T Washington

This is the autobiography of Mr Washington who was born into slavery. He taught himself to read and somehow developed a deep self-love and a belief that he could succeed. He believed in education and worked tirelessly in that field. His deep faith was a lived one.

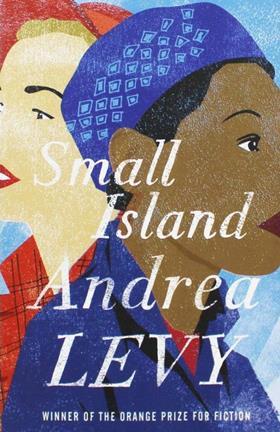

Small Island by Andrea Levy

I can still remember reading this book while on a bus and just laughing out loud uncontrollably. Having grown up in Jamaica, I could ‘see’ the characters described in the book and understood her humiliation. The experience of the main character was real and sad. The reality of racism I knew first han

No comments yet